Rats and the evolution of the dump

Back in the day, rats could be found at the various little dumps around town. The advent of modern sanitation methods improved this greatly.

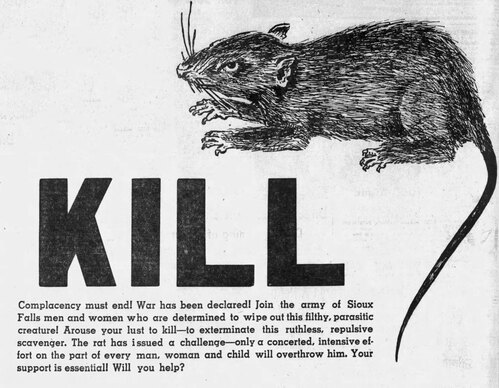

For residents of a city, proper sanitation is essential to control disease and increase quality of life. As far back as the early 1920s, Sioux Falls had an annual rat eradication program. Residents could pick up packets of poisoned materials for free from participating grocery stores. These packets would be distributed around their homes in the areas that rats frequented. The poison was supposed to be safe for children and pets and was, by necessity, slow acting to keep the critters coming back for more. The health department recommended leaving table scraps and bits of bread in the areas to gain the trust of the wee vermin. This raises the question: What happened to this annual program and the teams of rats that once ruled the dark alleys of this city?

To understand, we must look at how Sioux Falls used to handle its waste. In the early days of the 20th century, people may have burned their garbage. Those who didn’t, took it or had it taken to one of the dumps in the city. These dumps were often located in disused quarries or blank patches of land, and they were piled high with refuse. For a time, Sioux Falls’ largest and most used dump was north of the Riverside neighborhood on the east side of town, just south of the Big Sioux. It was on land owned by Sioux Falls Serum Co. and Sioux Falls Rendering Co. Each of these businesses owned a good quantity of hogs. Garbage haulers would dump their harvest on the east side of the dump one day, and the west side on the next. The hogs would be allowed to feed for free on the side that was closed for the day. It was good for the city to have a place for trash, and good for the land owners to have a place where their livestock could eat for free. The drawback was that all of the piled up trash was also attractive to thousands of rats, swarms of flies, and scavengers — citizens who were browsing the trash for treasures. This situation, as you can imagine, was not appealing to the people who built their homes in the Riverside neighborhood.

In 1946, a group calling itself The Riverside Improvement Club filed suit with the city, complaining that the dump was a health hazard.

The residential streets situated en route to the dump would collect garbage that either never made it all the way to the dump, or was taken by the wind into yards. The smell, the rats, and the flies did nothing to improve property values in the area.

Argus Leader staff writer Herb Qualset reported on the situation, observing, “Among these hogs, rats run about by the thousands. It was amusing to observe how the hogs and rats get along in the same feeding lot.” Both rat and hog had so much to eat that there was no need for one to bother the other, or humans in the area. “A human monster walking toward a garbage pile may at first scare these cute things a short distance away, but once they believe you mean no harm, they scamper toward you and may walk over your shoes and brush their tails against your leg just as friendly as the family cat does.”

In 1946, a group calling itself The Riverside Improvement Club filed suit with the city, complaining that the dump was a health hazard.

The residential streets situated en route to the dump would collect garbage that either never made it all the way to the dump, or was taken by the wind into yards. The smell, the rats, and the flies did nothing to improve property values in the area.

Argus Leader staff writer Herb Qualset reported on the situation, observing, “Among these hogs, rats run about by the thousands. It was amusing to observe how the hogs and rats get along in the same feeding lot.” Both rat and hog had so much to eat that there was no need for one to bother the other, or humans in the area. “A human monster walking toward a garbage pile may at first scare these cute things a short distance away, but once they believe you mean no harm, they scamper toward you and may walk over your shoes and brush their tails against your leg just as friendly as the family cat does.”

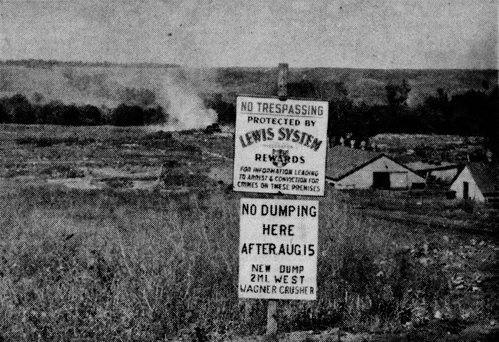

That same year the city bought a quarter section of land west of town near Ellis. Though it wasn’t mentioned to land owners in the area, this land was to be used as the city’s next dump. The residents in this area were not thrilled about this, and had the same complaints as those in Riverside. This would not be a hog-grazing dump, however. The city would use a new technique of sanitation known as a landfill. A trench would be dug, and throughout the day, the garbage haulers would dump their loads into this trench. Heavy equipment would be used to fill that trench with dirt from the next trench dug, and the process would begin anew. The garbage would not sit in the open and would not attract near the population of flies and rats as experienced at Riverside. Scavengers would not be allowed to browse the leavings dropped off there. Those near Ellis did not like the location of the city’s dump, but did not file suit.

Mayor V. L. Crusinberry dines with white linen and silver tea service at the landfill near Ellis in 1967 as a part of the "Clean-up, Fix-up, Paint-up" campaign. He is joined by upstanding members of the community and Chamber.

By 1978, the city’s landfill was nearly full. A new plot of land was arranged at the current location; 7 miles west of the city on 41st Street and half a mile south. The in-town dumps are no longer in operation, and the health department no longer needs to encourage citizens to pick up their rat poison at their favorite grocery stores.

Years ago, my sister's mother-in-law mentioned frequently seeing rats at the old Granada Theater when she was young. I wondered why this story wasn't still common, and writing this piece has helped me to understand.

Years ago, my sister's mother-in-law mentioned frequently seeing rats at the old Granada Theater when she was young. I wondered why this story wasn't still common, and writing this piece has helped me to understand.

© www.GreetingsFromSiouxFalls.com